O.C. public defender who exposed jailhouse snitch scandal is retiring, but not done

- Share via

Aerosmith, the Eagles and the Rolling Stones crooned from the speakers at Vacation Bar in Santa Ana last Thursday.

The gift table was near the entrance. Pizzas and cheesecake sat toward the back. At a photo booth, guests grabbed signs with all sorts of corny, apropos quips for a retirement party: Having fun is my new job. Still the boss. Goodbye to 9-5.

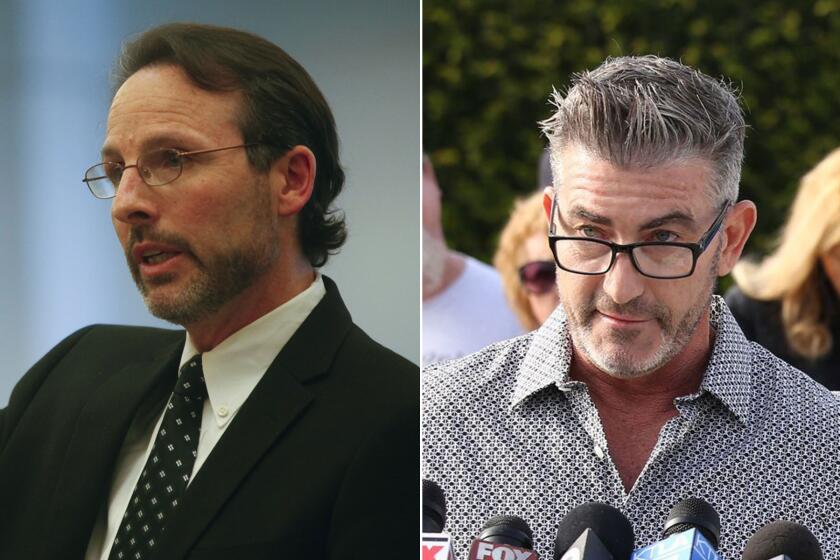

It seemed like any other boomer farewell. But when the lights dimmed for a film tribute to Scott Sanders, even a stranger could surmise that the man of the hour was no ordinary office jockey.

The longtime Orange County public defender changed local history in 2013 when he presented a judge with evidence that sheriff’s deputies had illegally used jailhouse snitches for decades.

U.S. Department of Justice report criticizes the Orange County Sheriff’s Department and the district attorney’s past use of jail informants.

Although prosecutors and law enforcement have long used jailhouse informants, they can’t be tapped once the defendant has been charged and has a lawyer. Sanders claimed that the O.C. District Attorney’s office repeatedly and knowingly violated this constitutional protection. Prosecutors, for their part, derided Sanders in court and to the press as a desperate hack willing to lie to defend Scott Dekraai, a client accused of massacring eight people at a Seal Beach salon.

But Sanders was right.

The judge, Thomas Goethals — a former homicide prosecutor — removed the D.A.’s office from the Dekraai case, saying he didn’t believe the office could ethically pursue it. In 59 other cases, charges were dropped, convictions overturned or sentences reduced because of what Sanders uncovered in the O.C. snitch scandal.

O.C. Sheriff Sandra Hutchens decided not to seek reelection in 2018 in the scandal’s aftermath, the same year that Tony Rackauckas — district attorney since 1999 and a titan in the O.C. legal world — lost his bid for a sixth term by a huge margin.

“What he did was a monumental kind of tilt — a legal earthquake,” said Jack Earley, an O.C. public defender during the 1970s who is most famous for representing La Jolla socialite Betty Broderick in the murders of her ex-husband and his new wife. “And Scott got there by doing the hard, dirty work a great public defender does.”

Applause and aws erupted as soon as the film tribute began. There were photos of a baby-faced Sanders on his first day on the job, fresh from stints working for the Peace Corps and for lawyers representing fishermen affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill. There were videos from bowling nights and rap battles with colleagues. The whoops were especially loud for editorial cartoons featuring Sanders and for screen grabs of headlines from across the country as his national profile rose.

The biggest applause came for the last image: Sanders’ new business card for the private practice he’s starting.

Over 100 people crammed into the sweltering Vacation Bar to celebrate him, while the establishment’s hipster regulars quizzically looked on. His family was there, of course, including a son who’s going to clerk for the L.A. County alternate public defender’s office. Many of the attendees were current or former public defenders or judges, nearly all of whom declined to talk to me on the record.

There were also folks like Paul Wilson, who lost his wife in the Seal Beach massacre and initially loathed Sanders until realizing the snitch scandal was real. The two went on to speak about their unlikely friendship at victims’ rights conferences across Southern California, and Wilson plans to help Sanders however he can.

“God bless him for being a warrior,” Wilson said. “Someone who is honest and works to the bone like Scott, I want him on my team.”

Matt Ferner was also there. He’s a former reporter who covered the snitch scandal for the Huffington Post.

“Scott’s work changed the trajectory of my life,” Ferner said. “He was patient with my questions and courageous with what he sought to prove. He’s an example of how to live and work, many times over.”

Clad in a football jersey that read “OCPD” and the number 32, to signify how many years he worked as a public defender, Sanders reveled in all the love. When he wasn’t hugging people or shaking their hand, he was being pulled to the photo booth.

“I feel lucky so many good people are here,” the 58-year-old said during one of his few quiet moments. “It’s been great to see all this support, but it also hurts. I’m not going to have them anymore day in, day out.”

Suddenly, Goethals cut in between us. His retirement on March 31, after seven years as an appellate judge, just so happened to fall on Sanders’ last day as a public defender.

“Write a good one about him,” Goethals told me with a laugh, “because he’s one of the good ones.”

Paul Wilson once loathed Scott Sanders, who defended the killer of Wilson’s wife. But the Orange County “snitch scandal” led to an unlikely friendship.

My wife was also there so we could both pay our respects to Sanders. He’s a longtime customer at her Santa Ana restaurant, Alta Baja Market, to the point that I know his current go-to order (esquites salad and water with ice in a chilled mason jar), and my wife affectionately calls him “Pinche Scott” for causing so much trouble. He frequently holes up at a back table for hours with his laptop and mounds of documents, stopping only to take calls outside while my wife’s workers keep an eye on his stuff.

I had a front-row seat to the unfolding snitch scandal through the cartoons I commissioned and the stories I edited for OC Weekly. What Sanders did — knock out a popular sheriff and district attorney in a law-and-order county — was unprecedented and gave progressive activists a dash of hope that Orange County was changing for the better. In the process, Sanders became something rare in O.C. politics: a bona fide hero.

“The first time I met him, I thought, ‘Oh my God, that’s Scott Sanders,’” said Rose Angulo, who joined the O.C. public defender’s office in 2017 after a stint as a federal public defender. She wore a button that said “Scott Sanders for D.A. 2022,” a gag campaign his colleagues created that year. “He would get walls of media attention, but he always had the same level of dedication to the cases that didn’t get any news, and dedication to the rest of us. To the end, he had the same energy as our law clerks.”

While my wife posed in the photo booth with Sanders, I caught up with his Alta Baja lunch buddy, public defender Brian Reznick.

“We’re gonna miss his leadership by example the most,” said the 17-year veteran. “He’d be doing a felony trial, yet take the time to discuss my cases with me. He didn’t have to do that.”

No matter how much I tried, I couldn’t snag a few minutes with Sanders. So I finally did what everyone else was doing: grabbed him and darted to the photo booth.

To the end, Sanders was getting results. Earlier this year, the O.C. Sheriff’s Department and District Attorney’s Office reached an agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice to reform their use of jailhouse informants. Last month, a San Diego judge called the actions of former O.C. prosecutor Ebrahim Baytieh — now an O.C. Superior Court judge — “reprehensible” in a murder case that had been transferred to San Diego because of the snitch scandal.

Those developments convinced Sanders that his work on the snitch scandal was finally, truly over — and it was time to begin putting L.A. County, where he has lived for decades, onto his anti-corruption radar.

I asked Sanders how he planned to spend his first days not being a public defender.

A giant grin spread across his face.

“I’m going to volunteer with the office for a week. Then, I’m going to find the most challenging cases I can find — murder, death penalty.”

Did he make a difference? He nodded vigorously.

“We instilled a fear that if you cheat, you will be found out at some time,” Sanders replied. “You can’t hide. There’s no time you can be comfortable cheating.”

Someone interrupted us. Sanders went back into the photo booth, looking like the happiest guy in the world.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.