- Share via

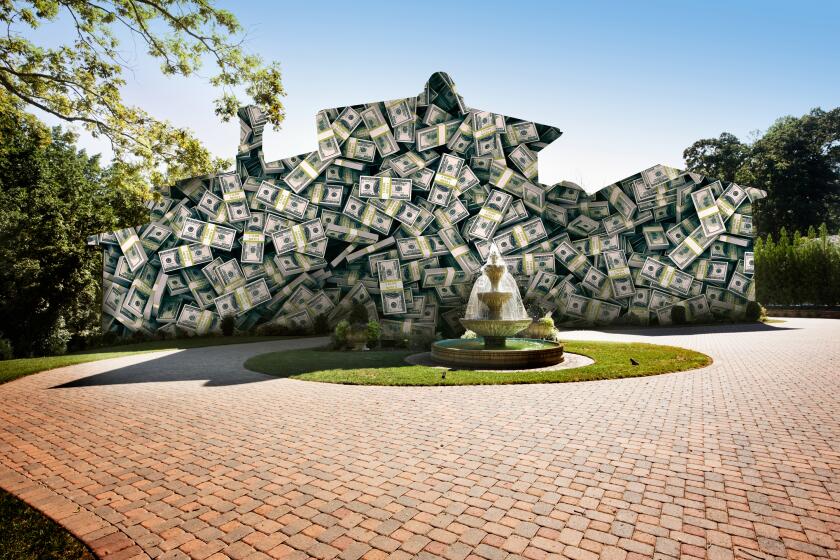

In 2022, Los Angeles voters approved Measure ULA, a transfer tax on the sale of high-value properties inside the city limits. Nicknamed the mansion tax by its supporters, Measure ULA imposed a 4% tax on sales over $5 million and a 5.5% tax on sales over $10 million — one of the steepest such levies in the nation. Its revenue is earmarked for low-income housing programs.

ULA’s tax is paid by sellers, which may explain why Mayor Karen Bass suggested suspending it after the wildfires. The mayor is right to worry. Property values in Pacific Palisades often top $5 million, creating concern that the tax could penalize owners who lost everything and just want to sell and move on. But Measure ULA’s problems run deeper. Suspended or not, it needs to be reformed.

L.A.’s tax on the sale of multimillion-dollar properties has collected about $480 million. It will be spent on affordable housing and tenant protection efforts.

Despite its nickname, ULA isn’t just a tax on mansions. It applies to nearly every property priced over $5 million, including apartment buildings, offices, soundstages, hotels and shopping centers — places Angelenos live, work and shop.

Additionally, ULA is not a tax on profit. It’s based on sale price. Thus, the owner of an office building that has plunged 90% in value since the COVID-19 pandemic might sell it for $15 million and incur an $825,000 ULA tax, despite the owner’s overall loss. On the other hand, someone who bought a house 10 years ago for $500,000 and sells today for $1.5 million would pay nothing. ULA’s design means large losses may be heavily taxed while big gains go scot free.

Measure ULA also has steep “cliffs” — thresholds where small price increases trigger massive tax increases. A property selling for $5 million incurs no ULA tax, but one selling for a dollar more pays $200,000. Such cliffs create strong incentives for owners to avoid the tax.

Measure ULA has raised more than $439 million since April 2023. A new data dashboard shows the sources of the funds.

The easiest way to avoid the tax is to not sell, and our research shows that over the first two years since ULA was implemented, high-value property sales in the city fell by about 50% — a far steeper decline than elsewhere in the county during the same period. Higher interest rates and construction costs aren’t to blame for the decline — those conditions affected the entire region. And while there was a temporary “rush to sell” before ULA was implemented, our analysis accounts for that behavior. The 50% drop is an effect of ULA specifically.

Depressed sales mean less revenue generated by ULA. Backers estimated ULA would raise $600 million to $1.1 billion annually. So far, collections have averaged just $288 million per year — less than half the lowest projections.

By reducing large sales, moreover, ULA has slowed the production of market-rate apartments. Most multifamily developments involve buying a suitable site and then selling the finished building. ULA can add significantly to the cost of both of those transactions. And because most market-rate housing developments now include some income-restricted affordable apartments provided by developers in exchange for increased project size, Los Angeles is getting fewer of those, too. Conservatively, we estimate ULA is costing the city more than 1,900 new units a year, of which at least 160 would have been affordable units produced without public funding. Meanwhile, the ULA revenue collected from newer multifamily projects since the tax went into effect is only enough to subsidize, at best, half that number. ULA’s poor design needlessly costs the city affordable housing.

The impact doesn’t stop at housing. ULA has also slowed large transactions for commercial, industrial and office properties. This effect, combined with the slowdown in residential transactions, is impeding property tax growth. Under California’s property tax system, local revenues increase primarily when properties are reassessed at sale. Large transactions contribute disproportionately to that growth. Sales over $5 million are only 4% of all transactions but account for more than 40% of the growth in the city’s tax base. Over time, fewer big transactions means less funding for all public agencies and programs that rely on L.A.’s tax base: schools, community colleges and the county and its safety-net programs.

Although the ballot language for Measure ULA included strong limits on the City Council’s power to amend it, ULA is fixable. The most effective approach may be state action. State governments almost always have the power to revoke or amend local actions, and transfer taxes are arguably an issue of interest to the state, because they have direct effects on California’s housing goals and overall fiscal health.

Measure ULA has raised hundreds of millions for affordable housing. But some nonprofits that provide affordable housing themselves are being blindsided by the tax.

Targeted state legislation could reduce ULA’s negative effects while preserving its goal of raising funds to help low-income renters. Options include restricting the tax to single-family homes (making it a true mansion fax), adopting marginal rates to eliminate the “cliffs” (to work similarly to income taxes ), or limiting ULA to properties that haven’t been sold or improved in many years; sales of these properties are much more likely to represent a large windfall for sellers and such sales would not tend to undermine housing and job creation.

Los Angeles needs housing and economic policies that work — especially as we recover from the January wildfires. That means balancing the urgent need for new revenue with policies that encourage new housing and jobs. Measure ULA, as currently structured, makes that balance harder to achieve. It could become a better tool — one that fulfills voters’ hopes for more affordable housing, strengthens the local economy and protects the social and fiscal foundation of the region.

Michael Manville is a professor of urban planning at UCLA and an affiliated scholar at its Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies. Shane Philips is housing initiative project manager at the Lewis Center. Jason Ward is co-director of the Rand Center on Housing and Homelessness.

More to Read

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- The authors argue that Measure ULA’s broad application to commercial properties, offices, and multifamily developments—not just mansions—has stifled real estate transactions, with a 50% decline in high-value sales within Los Angeles compared to unaffected areas of the county[1].

- They highlight tax cliffs as a critical flaw: a $1 increase from $5 million to $5,000,001 triggers a $200,000 tax, incentivizing sellers to avoid transactions or delay sales[1].

- The tax’s design penalizes properties sold at a loss (e.g., commercial buildings post-COVID) while exempting highly profitable lower-value sales, creating inequities[1].

- Measure ULA has underperformed revenue projections, generating $288 million annually—less than half the lowest estimates—due to reduced transaction activity[1].

- The authors claim the tax reduces housing production, costing Los Angeles over 1,900 market-rate units yearly (including 160 affordable units) while ULA-funded projects only offset half that loss[1].

- Proposed reforms include restricting the tax to single-family homes, adopting marginal tax rates, or targeting properties unreassessed for decades to avoid harming housing and job growth[1].

Different views on the topic

- Measure ULA has raised $632 million in two years, funding affordable housing construction, tenant protections, and homelessness prevention programs, with revenue increasing as legal challenges subside[4][3].

- Advocates emphasize its role in addressing Los Angeles’ housing crisis, including protecting 35,000 tenants from eviction and creating thousands of construction jobs[3][4].

- Opponents’ efforts to overturn the tax through lawsuits and ballot measures have largely failed, with courts upholding its constitutionality[2][3].

- While commercial sales initially dipped, supporters argue the decline reflects real estate industry tactics (e.g., pre-April 2023 sales rushes, off-market deals) rather than long-term structural issues[3][4].

- The tax’s proponents reject claims it harms housing production, noting that market-rate developers’ slowdowns are influenced more broadly by interest rates and construction costs, not ULA alone[4].

- Reforms proposed by critics, such as exempting multifamily developments, risk undermining the measure’s core goal of redistributing wealth from high-value transactions to fund equitable housing solutions[3][4].

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.