- Share via

What do Pennsylvania, Illinois, Nebraska, Mississippi, Michigan, Utah, Minnesota, Maine, South Carolina and Massachusetts — states that span U.S. regions and the political divide — have in common?

All 10 have seen recent attempts to redesign their state flags.

In Mississippi, public pressure led the state to abandon their Confederate-themed flag. In Massachusetts, a commission recommended that the state develop a new seal and flag that would be more “aspirational and inclusive of the diverse perspectives, histories, and experiences” of its residents. Minnesota’s flag, once described as a “cluttered, genocidal mess,” featured the state seal — a white farmer working in a field with a Native American on a horse in the background — surrounded by trees, a stream, stars, circles, meaningful dates and more. The new blue and white flag is far simpler. It has a dark blue section in the shape of the state next to a light blue section representing the state’s many lakes; in the center is a white star.

California’s bear flag pays tribute to white settlers who revolted against Mexico and left a trail of violence against the Indigenous population.

Some of these 10 flag redesign efforts have succeeded (Minnesota, Mississippi, Utah); some have not (Maine, Massachusetts); and others are ongoing. In states that adopted new flags, some citizens and lawmakers have started campaigns to bring the old flag back. Citizens in additional states such as Washington are pushing their lawmakers to join in the redesign game, too.

You might think Americans wouldn’t care much about what’s on their state flags. But studying state identities has taught me that it doesn’t take much to stir people up about the symbols that represent them. A mere mention of my research, or of flags that are SOBs (state “seals on bedsheets”), or of the curious fact that some people get tattoos of the shape of their state, leads to an outpouring of anecdotes, questions and confessions. As one social media account that promotes the new Utah flag once posted: “Nobody cares about flags. Until they do. Everybody cares about flags.”

There is something about states that tugs at people. Where we live or where we were born shapes how we see ourselves and others. It grounds us, makes us part of a political community in ways we are only beginning to understand. As I’ve learned, people’s psychological attachments to their states can promote unity, trust and civic engagement. And the fact that so many states are in the process of reevaluating their identities, as the flag redesigns indicate, is no coincidence.

Nicholas Goldberg: Why make the grizzly bear California’s state animal — after they’re all gone?

On the 100th anniversary of the last shooting of a wild grizzly in the state, you’ve got to wonder why the bears we exterminated were made the symbol of the state.

A confluence of developments is making state politics and history, and their symbolic representation, particularly salient today. One is the overall nationalization of politics, the growing alignment in how people vote across federal, state and local offices, along with a greater focus on national politics in local news. Increasingly, citizens are contending with hot-button national issues — immigration, gun control, abortion, voting rights and more — in state and local spaces. And with increasing political polarization in Congress, federal gridlock on these issues seems to have enhanced states’ roles as sites of vibrant policymaking. Meanwhile, rapidly changing demographics, along with movements for racial and historical justice, have brought new perspectives to established state imagery.

My research shows that a majority of Americans — 58% — consider their state to be very or somewhat important to their identity. That’s similar to the importance people place on other politically relevant identities, such as party membership, race, economic class and religion. I’ve also found that state identities are not apolitical, however much we might think they would be primarily about fun stuff like nature, food, music and sports teams.

In fact, people are more likely to say that their state is an important part of their identity if they align with the state’s partisan bent, red or blue. And although political considerations don’t emerge all that strongly when people are asked to explain why they feel connected to their state, they emerge quite forcefully when people discuss what they wish were different there — from political leadership and tax rates to the cost of living and the ideological makeup of the electorate.

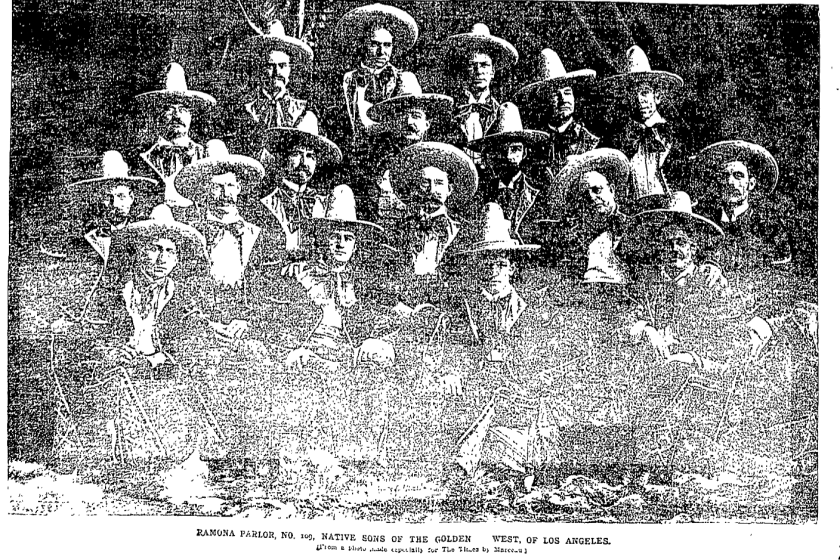

The Native Sons of the Golden West have worked for nearly 150 years to preserve state history. They also spent much of the early 1900s pushing anti-Asian, white supremacist policies.

We still have a lot to learn about the political consequences of people’s state identities. But scholars already have found that strong state identities improve trust in government and increase people’s willingness to share limited resources with fellow state residents over others.

For example, if you identify strongly with your state, it can improve your view of your governor, especially if you aren’t a member of their political party. People with high levels of state pride are also more likely to support spending on healthcare, education, infrastructure and transportation. And they are more willing to engage in local civic and political acts, such as volunteering, attending a government meeting and contacting elected officials.

One important question to consider in future research relates to ingroups and outgroups. Strong state identification doesn’t seem to be born out of resentment toward a clear outgroup, which means it might be less likely to fuel political conflicts than other group identities, such as race, partisanship and the urban/rural divide.

As often happens in the annals of California innovation, the story of how one of the state’s last grizzly bears came to be a global fashion icon begins in an 8-by-8 foot garage.

The most salient outgroup for state ingroups may be the national government, but it is not clear that this relationship is particularly or uniformly adversarial. As legal scholar Jessica Bulman-Pozen explains, finding connection with a state can serve as a proxy for national identity in a time when people feel that government is deviating from their hopes for the country.

A Washington Post columnist displayed this sentiment after the 2024 election in an op-ed titled, “My Blue State Is My Country Now,” expressing her pride in New York’s ability to stand for the values, rights and opportunities she feels all Americans deserve. In other ingroup/outgroup dynamics, people generally don’t see themselves as part of both groups, but here the author claimed her New York and her American identities, allowing her to express aspirations for both instead of pitting them against each other.

Is it possible that a strong connection to one’s state can help overcome more fraught divisions without accentuating outgroup animosity? Could American federalism, which is so often associated with fragmentation and divergence, be a force that helps keep people together in turbulent times? As one state senator in Utah put it when he was asked if remaking the flag was the best use of government time: “When you connect the values [we hold] with the symbols on the flag, we’re going to have a rallying point for the entire state. I’m really looking forward to taking the identity of what it means to be from Utah to the next level of something we can all unite behind.”

Deborah J. Schildkraut is a political science professor at Tufts University. This article was produced in partnership with Zócalo Public Square.

More to Read

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- State symbols, particularly flags, serve as powerful tools for fostering unity and civic engagement, with 58% of Americans considering their state identity significant to their sense of self[1].

- Redesigning state flags to reflect inclusivity and aspirational values—such as Minnesota’s simplified design replacing a historically problematic seal—aligns with movements for racial and historical justice, enhancing residents’ pride in their state’s evolving identity[1].

- Strong state identities may improve trust in local governance and encourage support for state-level policies on healthcare, education, and infrastructure, even among those who disagree with their governor’s party affiliation[1].

- Federal gridlock has elevated states’ roles as laboratories for policymaking, allowing state identities to act as proxies for national aspirations, as seen in post-2024 electoral sentiments like “My Blue State Is My Country Now”[1].

Different views on the topic

- Critics argue that legislative focus on symbolic changes, such as flag redesigns, distracts from pressing policy issues like healthcare or economic inequality, calling such efforts performative or trivial[1][2].

- Redesigns risk alienating groups attached to historical symbols, sparking backlash campaigns to restore older flags (e.g., Maine and Mississippi), which can deepen cultural divides rather than mend them[1][3].

- National symbols, including state flags, often reflect dominant cultural narratives, potentially excluding marginalized perspectives and reinforcing exclusionary identities despite intentions of inclusivity[2][3].

- Overemphasis on state identity could inadvertently fuel resentment toward the federal government or other states, complicating efforts to address nationwide challenges collaboratively[2][3].

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.